Wednesday, September 30, 2009

amanda fucking palmer » blog:

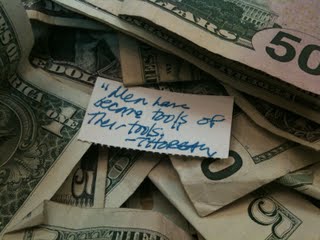

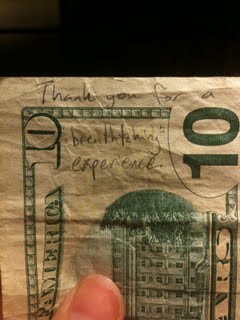

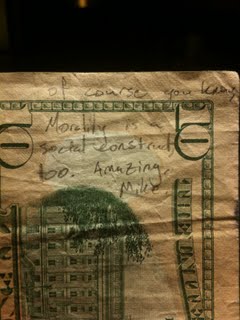

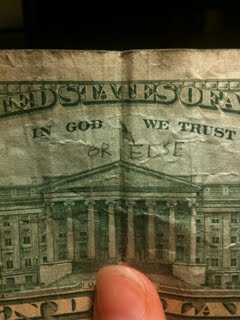

i can’t help it: i come from a street performance background. i spent years gradually building up a tolerance to the inbuilt shame that society puts on laying your hat/tipjar on the ground and asking the public to support your art.

and for the last 10 years, i have been working my ass off in a different way: tirelessly making music, traveling the world, connecting with people, trying to keep my balance, almost never taking a break and, frankly, not making a fortune doing it. i still struggle to pay my rent sometimes. i’m still more or less in debt from my last record. i’ll lay it all out for you in another blog. it’s just math.

if you think i’m going to pass up a chance to put my hat back down in front of the collected audience on my virtual sidewalk and ask them to give their hard-earned money directly to me instead of to roadrunner records, warner music group, ticketmaster, and everyone else out there who’s been shamelessly raping both fan and artist for years, you’re crazy.

the critics are welcome to criticize.

they do not have to attend the party.

and even if they attend the party with rolling eyes, they will not be charged.

they will be hugged, they will be accepted and entertained, and they will not be given the hairy eyeball if they leave the room without tipping.

chances are they’ll tell a friend about the next party, and their friend will probably leave a dollar. and tell someone else.

taking my stand as a virtual street performer is the best thing that’s happened to my career and i revel in it.

and i love bringing people along for the ride.

i believe in the future of cheap art, creative enterprise, and an honorable public who will put their money where there mouth is, or rather, their spare change where their heart is.

i can’t help it: i come from a street performance background. i spent years gradually building up a tolerance to the inbuilt shame that society puts on laying your hat/tipjar on the ground and asking the public to support your art.

and for the last 10 years, i have been working my ass off in a different way: tirelessly making music, traveling the world, connecting with people, trying to keep my balance, almost never taking a break and, frankly, not making a fortune doing it. i still struggle to pay my rent sometimes. i’m still more or less in debt from my last record. i’ll lay it all out for you in another blog. it’s just math.

if you think i’m going to pass up a chance to put my hat back down in front of the collected audience on my virtual sidewalk and ask them to give their hard-earned money directly to me instead of to roadrunner records, warner music group, ticketmaster, and everyone else out there who’s been shamelessly raping both fan and artist for years, you’re crazy.

the critics are welcome to criticize.

they do not have to attend the party.

and even if they attend the party with rolling eyes, they will not be charged.

they will be hugged, they will be accepted and entertained, and they will not be given the hairy eyeball if they leave the room without tipping.

chances are they’ll tell a friend about the next party, and their friend will probably leave a dollar. and tell someone else.

taking my stand as a virtual street performer is the best thing that’s happened to my career and i revel in it.

and i love bringing people along for the ride.

i believe in the future of cheap art, creative enterprise, and an honorable public who will put their money where there mouth is, or rather, their spare change where their heart is.

Apple Genius Bar: iPhones' 30% Call Drop Is "Normal" in New York - Apple - Gizmodo:

Giz reader Manoj took his iPhone to the Genius Bar to have it looked at because it was dropping calls left and right, and AT&T swore stuff was totally kosher on their end, so he thought something was wrong with his phone. After doing a stat dump, the Genius showed Manoj that his iPhone had actually dropped 22 percent of calls.

The jawdropper: The Genius told Manoj that's actually excellent compared to most people in the New York area, where a 30 percent dropped call rate is the average. There was nothing Apple could do for Manoj. His phone was totally fine. Which means there's nothing Apple can do for rest of us.

Ridiculous, and downright insulting.

Giz reader Manoj took his iPhone to the Genius Bar to have it looked at because it was dropping calls left and right, and AT&T swore stuff was totally kosher on their end, so he thought something was wrong with his phone. After doing a stat dump, the Genius showed Manoj that his iPhone had actually dropped 22 percent of calls.

The jawdropper: The Genius told Manoj that's actually excellent compared to most people in the New York area, where a 30 percent dropped call rate is the average. There was nothing Apple could do for Manoj. His phone was totally fine. Which means there's nothing Apple can do for rest of us.

Ridiculous, and downright insulting.

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

Microsoft's grinning robots or the Brotherhood of the Mac. Which is worse? · cleversimon.com:

Charlie Brooker’s thesis is “I hate Windows, but I hate strawmen Mac evangelists more, so I’m going to marinate in my misery just to stick it to these imaginary fanboys. I’m unhappy and unproductive, and I’m going to stay unhappy and unproductive—that’ll show ‘em.”

Finishing the sentence “I’ll never buy a Mac because” with anything but “it doesn’t meet my needs” means you don’t get to accuse Apple users of making irrational purchasing decisions based on slavish adherence to an ideology.

Charlie Brooker’s thesis is “I hate Windows, but I hate strawmen Mac evangelists more, so I’m going to marinate in my misery just to stick it to these imaginary fanboys. I’m unhappy and unproductive, and I’m going to stay unhappy and unproductive—that’ll show ‘em.”

Finishing the sentence “I’ll never buy a Mac because” with anything but “it doesn’t meet my needs” means you don’t get to accuse Apple users of making irrational purchasing decisions based on slavish adherence to an ideology.

Monday, September 28, 2009

Entangled Giant - The New York Review of Books:

But the momentum of accumulating powers in the executive is not easily reversed, checked, or even slowed. It was not created by the Bush administration. The whole history of America since World War II caused an inertial transfer of power toward the executive branch. The monopoly on use of nuclear weaponry, the cult of the commander in chief, the worldwide network of military bases to maintain nuclear alert and supremacy, the secret intelligence agencies, the entire national security state, the classification and clearance systems, the expansion of state secrets, the withholding of evidence and information, the permanent emergency that has melded World War II with the cold war and the cold war with the "war on terror"—all these make a vast and intricate structure that may not yield to effort at dismantling it. Sixty-eight straight years of war emergency powers (1941–2009) have made the abnormal normal, and constitutional diminishment the settled order.

But the momentum of accumulating powers in the executive is not easily reversed, checked, or even slowed. It was not created by the Bush administration. The whole history of America since World War II caused an inertial transfer of power toward the executive branch. The monopoly on use of nuclear weaponry, the cult of the commander in chief, the worldwide network of military bases to maintain nuclear alert and supremacy, the secret intelligence agencies, the entire national security state, the classification and clearance systems, the expansion of state secrets, the withholding of evidence and information, the permanent emergency that has melded World War II with the cold war and the cold war with the "war on terror"—all these make a vast and intricate structure that may not yield to effort at dismantling it. Sixty-eight straight years of war emergency powers (1941–2009) have made the abnormal normal, and constitutional diminishment the settled order.

Friday, September 25, 2009

Thursday, September 24, 2009

Apple’s Secrecy Strategy Ain’t Easy (MS Pink Phones) | Cult of Mac:

And this is why Apple’s ability to create, sustain, and often exceed hype is such a remarkable thing. There have been leaks at times, but nothing this big, ever. Instead, Apple manages to stoke the rumor fires just enough that we all have some notion of what it might make next — we’re all convinced that Apple’s making a tablet — but none of us have any idea of what the actual thing will be. We don’t even know which operating system such a tablet will run.

Maintaining that mystique requires incredible loyalty from your employees, extreme paranoia, and even an unwillingness to let any of your partners touch or see the final devices. It’s the stumbles of Apple’s competitors that remind me just how special Steve Jobs and team are when they’re at the top of their game. The reason the entire tech media corps went insane for the iPhone was that it was a great product and a huge surprise at once.

And this is why Apple’s ability to create, sustain, and often exceed hype is such a remarkable thing. There have been leaks at times, but nothing this big, ever. Instead, Apple manages to stoke the rumor fires just enough that we all have some notion of what it might make next — we’re all convinced that Apple’s making a tablet — but none of us have any idea of what the actual thing will be. We don’t even know which operating system such a tablet will run.

Maintaining that mystique requires incredible loyalty from your employees, extreme paranoia, and even an unwillingness to let any of your partners touch or see the final devices. It’s the stumbles of Apple’s competitors that remind me just how special Steve Jobs and team are when they’re at the top of their game. The reason the entire tech media corps went insane for the iPhone was that it was a great product and a huge surprise at once.

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Katie Couric's salary exceeds combined budgets of NPR's top news shows - Boing Boing:

Michael Massing of the Columbia Journalism Review digs up some startling info that helps explain why network TV news is knee-deep in FAIL while National Public Radio thrives:

Katie Couric's annual salary is more than the entire annual budgets of NPR's Morning Edition and All Things Considered combined. Couric's salary comes to an estimated $15 million a year; NPR spends $6 million a year on its morning show and $5 million on its afternoon one. NPR has seventeen foreign bureaus (which costs it another $9.4 million a year); CBS has twelve. Few figures, I think, better capture the absurd financial structure of the network news.

Michael Massing of the Columbia Journalism Review digs up some startling info that helps explain why network TV news is knee-deep in FAIL while National Public Radio thrives:

Katie Couric's annual salary is more than the entire annual budgets of NPR's Morning Edition and All Things Considered combined. Couric's salary comes to an estimated $15 million a year; NPR spends $6 million a year on its morning show and $5 million on its afternoon one. NPR has seventeen foreign bureaus (which costs it another $9.4 million a year); CBS has twelve. Few figures, I think, better capture the absurd financial structure of the network news.

Tuesday, September 22, 2009

France gives final approval to three-strikes law | Electronista:

The system won't give those accused full access to the court system but should still give them a 'fast track' system that still lets them defend themselves. An initially proposed system would have handed all control of the punishment to a non-legal authority and was rejected as unconstitutional earlier this year, forcing a modification to accommodate basic legal rights.

Critics still maintain that the system is skewed heavily in favor of the accusing music labels and movie studios, which can disrupt a user without definitive proof that links a particular person to an Internet connection. They have also argued the bill represents a violation of piracy by encouraging media organizations to scan users' Internet traffic without their consent and that it ignores the increasing nature of Internet access as an important utility.

The system won't give those accused full access to the court system but should still give them a 'fast track' system that still lets them defend themselves. An initially proposed system would have handed all control of the punishment to a non-legal authority and was rejected as unconstitutional earlier this year, forcing a modification to accommodate basic legal rights.

Critics still maintain that the system is skewed heavily in favor of the accusing music labels and movie studios, which can disrupt a user without definitive proof that links a particular person to an Internet connection. They have also argued the bill represents a violation of piracy by encouraging media organizations to scan users' Internet traffic without their consent and that it ignores the increasing nature of Internet access as an important utility.

Sunday, September 20, 2009

Where's the world's best food?:

The Guardian lists the best 50 foods to eat and where to get them. I've had a few of these (ravioli at Babbo, pork at Gramercy, pho at Pho 24, pastrami at Katz's, etc.) but, sucker that I am for such things, I particularly enjoyed reading about the Turkish olive oil available at an electrical supply shop in London.

The Guardian lists the best 50 foods to eat and where to get them. I've had a few of these (ravioli at Babbo, pork at Gramercy, pho at Pho 24, pastrami at Katz's, etc.) but, sucker that I am for such things, I particularly enjoyed reading about the Turkish olive oil available at an electrical supply shop in London.

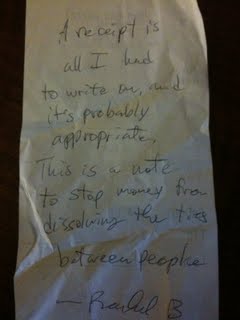

Jim Rutter's Twitter response to my critique from the other day:

Like a lot of Twitter posting, this sounds good in 140 characters but makes very little sense.

In my original post I linked to his full review, so that it could be assessed alongside my critique. I quoted nothing out of context, and I didn't use information out of context in assessing the review--Mr. Rutter's affiliation with the Libertarian party is a matter of public record, and appears on the bio he provides for the site where he reviews. The arguments I made are sound, clear, and supported by audio recordings of the show and the talkback.

Also, let's be clear about the power relationship: when an artist has the temerity to respond to a critic, the artist is the one in a position to take a fall. A critic has an implied and express trust that their work is even-handed and aesthetically sound, and if an artist challenges that, especially in a review about their own work, they will probably lose. Tactically it is always better to concede and move on, especially from a poor review on a website in a city I do not live in—drawing attention to writers who despise your work is not tactically sound.

I didn't do that because I felt the discussion was worth it in this case—that the formal issues of rigor and bias were worth commenting on, and using it as an opportunity to reflect on the state of our criticism. I will probably pay for this.

What I'm saying is that I have no "dirty tricks" to play—I'm the artist whose work was reviewed. I have been thorough, polite, and I am the one who risks by engaging in discussion. If Mr. Rutter believes my response is full of "dirty tricks", he is deeply mistaken.

Given the disappointing tenor of this response, barring the unforeseen this will be my last word on the matter.

Like a lot of Twitter posting, this sounds good in 140 characters but makes very little sense.

In my original post I linked to his full review, so that it could be assessed alongside my critique. I quoted nothing out of context, and I didn't use information out of context in assessing the review--Mr. Rutter's affiliation with the Libertarian party is a matter of public record, and appears on the bio he provides for the site where he reviews. The arguments I made are sound, clear, and supported by audio recordings of the show and the talkback.

Also, let's be clear about the power relationship: when an artist has the temerity to respond to a critic, the artist is the one in a position to take a fall. A critic has an implied and express trust that their work is even-handed and aesthetically sound, and if an artist challenges that, especially in a review about their own work, they will probably lose. Tactically it is always better to concede and move on, especially from a poor review on a website in a city I do not live in—drawing attention to writers who despise your work is not tactically sound.

I didn't do that because I felt the discussion was worth it in this case—that the formal issues of rigor and bias were worth commenting on, and using it as an opportunity to reflect on the state of our criticism. I will probably pay for this.

What I'm saying is that I have no "dirty tricks" to play—I'm the artist whose work was reviewed. I have been thorough, polite, and I am the one who risks by engaging in discussion. If Mr. Rutter believes my response is full of "dirty tricks", he is deeply mistaken.

Given the disappointing tenor of this response, barring the unforeseen this will be my last word on the matter.

Saturday, September 19, 2009

Scrappy Days - Page 6:

Scrappy did exactly what he was supposed to do: He got Scooby Doo renewed for another season. I don't think he was a good addition to the format and the fact that he could talk, while his Uncle Scooby sorta couldn't, tore the already-frail "reality," to use that word in the loosest-possible manner. Then again, the underlying premise of "there's no such thing as ghosts" was shredded somewhat during the seasons that the show had guest stars and so Scooby was teaming up with Speed Buggy (a talking car) and Jeannie (a genie). Later, of course, they gave up altogether on the notion that the supernatural did not exist and had Scooby and Shaggy chased by real werewolves and mummies and space aliens.

Scrappy did exactly what he was supposed to do: He got Scooby Doo renewed for another season. I don't think he was a good addition to the format and the fact that he could talk, while his Uncle Scooby sorta couldn't, tore the already-frail "reality," to use that word in the loosest-possible manner. Then again, the underlying premise of "there's no such thing as ghosts" was shredded somewhat during the seasons that the show had guest stars and so Scooby was teaming up with Speed Buggy (a talking car) and Jeannie (a genie). Later, of course, they gave up altogether on the notion that the supernatural did not exist and had Scooby and Shaggy chased by real werewolves and mummies and space aliens.

Friday, September 18, 2009

In Philadelphia I had the interesting opportunity to find out what would happen if HOW THEATER FAILED AMERICA was reviewed by an avowed Libertarian.

What I learned is an old lesson: good criticism relies on rigor, analysis, reporting, and an awareness of ideological blind spots. This review by Jim Rutter has none of these qualities.

As is my usual technique when I do these infrequent responses, I will refrain from commenting on the aesthetic assessment of the work, and simply address the portions of the review that pertain to the arguments of the piece.

The review starts, strangely, with a review of the post-show discussion:

“During the audience discussion following Mike Daisey’s monologue about the market forces that have ruined regional theater in America, a young woman asked Daisey how he could reach more young people with his message about theater and hope.

“Lower the ticket prices,” Daisey replied. To which Nick Stuccio, director of the Live Arts festival, shouted back from his seat: “They’re 15 dollars!”

So much for Daisey’s understanding of the simple economic concept of price elasticity.”

I am well aware of price elasticity, but the simple fact is that the tickets are not 15 dollars: they were $25 and $30 for each night of the show. Elemental fact-checking on Rutter’s part should have discovered that. Discounts may be available, but I address the weakness of discounting in the piece itself, and I won’t repeat myself here. I stand by the answer that within the context of the Philadelphia Live Arts Festival and its collision of a curated festival with a traditional fringe, that ticket price is a roadblock.

Rutter will however go on to distort this comment I made in an aftershow discussion, in response to a specific question from a student, as a basis for dismissing my understanding of my workplace wholesale.

To base the show’s assessment on a post-show discussion indicates, at best, a confusion about basic protocol about art and framing. At worst it’s simply unethical, as it indicates a desire to twist the art until it can be quickly dismissed on an ideological basis.

Rutter summarizes my assessment of the economic situation in the American theater as follows:

“As for economics, Daisey bemoans the theater as a slaughterhouse rather than a workplace, where few artists can make a sufficiently decent living to settle down and raise a family. He condemns regional theaters that abandoned local artists in favor of New York actors, a practice that, he argues, resulted in a massive disconnect between actors and communities, and an unsustainable situation where audiences “are drying up and dying off.” Mostly, Daisey laments that America’s theaters have become corporations packaging and commodifying their art.”

This is largely accurate, and he appears to take no issue with this assessment. He continues:

“How would Daisey solve this problem? He wants to lower ticket prices to create greater accessibility for audiences, while at the same time producing compelling art and paying actors a living wage— a strategy that, as I recall, was a resounding success in Soviet Russia.”

This would be damning, if in fact I said anything resembling this in the monologue. I do not posit some magical solution to an incredibly complex and difficult economic issues that afflicts my field.

The question of ticket prices is a complex one, and I talk at some length about the complexities of it in the piece—from ever-increasing discounts based on age, to the fact that theaters crave new audiences but are terrified by the change that will bring.

I do point out that our current emphasis is in the pouring of resources into buildings in terms of capital development, and we do not invest in people or art to any degree—and the brain drain that results from this is choking off the theater, and stifling our ability to make a thriving future.

“Daisey further laments that theater companies pay more to development and marketing professionals than to artists. But how else are theater troupes supposed to raise funds? Even Jesus lacked much of a following until the Apostle Paul revved up his PR machine.”

This is reductive and untrue. I do lament that we pay theater workers far below a living wage…but the answer is not to turn on each other and try to strip other workers in the theater of THEIR sub-market wages.

It’s not as though ANYONE is getting rich working in the non-profit theater, and the piece is exceedingly clear about this, and about my respect and admiration for everyone who dedicates themselves to the theater in all ways. Only someone who is not aggressively not listening, and interesting in portraying my position as divisive would believe I said anything like this.

“I walked out of the Suzanne Roberts Theatre into a sea of coeds on Broad Street sporting short skirts and baggy pants— young, full of life, and bursting with the confident knowledge that the world is still waiting to open up to them. No doubt they had just emerged from watching Transformers in a movie theater before heading for a pitcher of beer at a bar. Not a bad way for kids to spend 15 measly bucks.

What, by contrast, would compel any mentally healthy 20-year-old to attend a highly acclaimed (albeit depressing) American classic like, say, The Glass Menagerie— even if admission was free?”

This disconnect is featured in the monologue prominently—the idea that the work can adapt to change without fundamentally examining the assumptions of our theater, and that change is inevitable and must be confronted. I wouldn’t put it with the same degree of cynicism that Mr. Rutter uses, but fundamentally he is not at all wrong that the American theater fails to make itself relevant to the culture at large.

Finally, there is a virulent anti-actor bigotry in the writing—his writing is laced with expressions like:

“He succeeds in demonstrating only that actors know nothing about economics.”

“Why do I doubt that an actor can supply the answer?”

It is as familiar as it is tired—I’m sure Mr. Rutter loves watching actors on stage, so long as they know their place and keep their mouths shut. The problem isn't the bias—we all have bias—but his inability to recognize or address it in the writing.

Mr. Rutter has chosen in this review not to engage in critical discourse, but to indulge his biases. He was predisposed by his political beliefs, and used whatever tools were available, including reaching outside the art itself, to find copy that could be distorted until it made his thesis stick. I suspect his motivations are connected to his ideology, and tied to his pride in his training in economics, which he is not shy about sharing in his writing.

Why would someone so well educated engage in such a sloppy indictment?

Because it is a theater review. It is writing utterly without consequences or conversation. There is no healthy discourse in our theatrical culture. Healthier art forms engage in actual dialogue—critical assessments are more than the final word, but the beginning of a true conversation. Critics can expect responses.

In the theater, bound by space and time specificness, criticism is often the final word—and with a lack of discourse, it pales and withers. Most disappointingly we teach our critics that there is no need for rigor, because there are no consequences or feedback. Crushed between the twin rocks of grim journalism and the grim theater, they are under tremendous pressure, and the field is responding by flattening, emptying out and vanishing.

Mr. Rutter seems like he could be an intelligent writer, and we need every sharp writer we can get in the theater. One can hope that his criticism in the future will rise above what he turned in on this occasion.

What I learned is an old lesson: good criticism relies on rigor, analysis, reporting, and an awareness of ideological blind spots. This review by Jim Rutter has none of these qualities.

As is my usual technique when I do these infrequent responses, I will refrain from commenting on the aesthetic assessment of the work, and simply address the portions of the review that pertain to the arguments of the piece.

The review starts, strangely, with a review of the post-show discussion:

“During the audience discussion following Mike Daisey’s monologue about the market forces that have ruined regional theater in America, a young woman asked Daisey how he could reach more young people with his message about theater and hope.

“Lower the ticket prices,” Daisey replied. To which Nick Stuccio, director of the Live Arts festival, shouted back from his seat: “They’re 15 dollars!”

So much for Daisey’s understanding of the simple economic concept of price elasticity.”

I am well aware of price elasticity, but the simple fact is that the tickets are not 15 dollars: they were $25 and $30 for each night of the show. Elemental fact-checking on Rutter’s part should have discovered that. Discounts may be available, but I address the weakness of discounting in the piece itself, and I won’t repeat myself here. I stand by the answer that within the context of the Philadelphia Live Arts Festival and its collision of a curated festival with a traditional fringe, that ticket price is a roadblock.

Rutter will however go on to distort this comment I made in an aftershow discussion, in response to a specific question from a student, as a basis for dismissing my understanding of my workplace wholesale.

To base the show’s assessment on a post-show discussion indicates, at best, a confusion about basic protocol about art and framing. At worst it’s simply unethical, as it indicates a desire to twist the art until it can be quickly dismissed on an ideological basis.

Rutter summarizes my assessment of the economic situation in the American theater as follows:

“As for economics, Daisey bemoans the theater as a slaughterhouse rather than a workplace, where few artists can make a sufficiently decent living to settle down and raise a family. He condemns regional theaters that abandoned local artists in favor of New York actors, a practice that, he argues, resulted in a massive disconnect between actors and communities, and an unsustainable situation where audiences “are drying up and dying off.” Mostly, Daisey laments that America’s theaters have become corporations packaging and commodifying their art.”

This is largely accurate, and he appears to take no issue with this assessment. He continues:

“How would Daisey solve this problem? He wants to lower ticket prices to create greater accessibility for audiences, while at the same time producing compelling art and paying actors a living wage— a strategy that, as I recall, was a resounding success in Soviet Russia.”

This would be damning, if in fact I said anything resembling this in the monologue. I do not posit some magical solution to an incredibly complex and difficult economic issues that afflicts my field.

The question of ticket prices is a complex one, and I talk at some length about the complexities of it in the piece—from ever-increasing discounts based on age, to the fact that theaters crave new audiences but are terrified by the change that will bring.

I do point out that our current emphasis is in the pouring of resources into buildings in terms of capital development, and we do not invest in people or art to any degree—and the brain drain that results from this is choking off the theater, and stifling our ability to make a thriving future.

“Daisey further laments that theater companies pay more to development and marketing professionals than to artists. But how else are theater troupes supposed to raise funds? Even Jesus lacked much of a following until the Apostle Paul revved up his PR machine.”

This is reductive and untrue. I do lament that we pay theater workers far below a living wage…but the answer is not to turn on each other and try to strip other workers in the theater of THEIR sub-market wages.

It’s not as though ANYONE is getting rich working in the non-profit theater, and the piece is exceedingly clear about this, and about my respect and admiration for everyone who dedicates themselves to the theater in all ways. Only someone who is not aggressively not listening, and interesting in portraying my position as divisive would believe I said anything like this.

“I walked out of the Suzanne Roberts Theatre into a sea of coeds on Broad Street sporting short skirts and baggy pants— young, full of life, and bursting with the confident knowledge that the world is still waiting to open up to them. No doubt they had just emerged from watching Transformers in a movie theater before heading for a pitcher of beer at a bar. Not a bad way for kids to spend 15 measly bucks.

What, by contrast, would compel any mentally healthy 20-year-old to attend a highly acclaimed (albeit depressing) American classic like, say, The Glass Menagerie— even if admission was free?”

This disconnect is featured in the monologue prominently—the idea that the work can adapt to change without fundamentally examining the assumptions of our theater, and that change is inevitable and must be confronted. I wouldn’t put it with the same degree of cynicism that Mr. Rutter uses, but fundamentally he is not at all wrong that the American theater fails to make itself relevant to the culture at large.

Finally, there is a virulent anti-actor bigotry in the writing—his writing is laced with expressions like:

“He succeeds in demonstrating only that actors know nothing about economics.”

“Why do I doubt that an actor can supply the answer?”

It is as familiar as it is tired—I’m sure Mr. Rutter loves watching actors on stage, so long as they know their place and keep their mouths shut. The problem isn't the bias—we all have bias—but his inability to recognize or address it in the writing.

Mr. Rutter has chosen in this review not to engage in critical discourse, but to indulge his biases. He was predisposed by his political beliefs, and used whatever tools were available, including reaching outside the art itself, to find copy that could be distorted until it made his thesis stick. I suspect his motivations are connected to his ideology, and tied to his pride in his training in economics, which he is not shy about sharing in his writing.

Why would someone so well educated engage in such a sloppy indictment?

Because it is a theater review. It is writing utterly without consequences or conversation. There is no healthy discourse in our theatrical culture. Healthier art forms engage in actual dialogue—critical assessments are more than the final word, but the beginning of a true conversation. Critics can expect responses.

In the theater, bound by space and time specificness, criticism is often the final word—and with a lack of discourse, it pales and withers. Most disappointingly we teach our critics that there is no need for rigor, because there are no consequences or feedback. Crushed between the twin rocks of grim journalism and the grim theater, they are under tremendous pressure, and the field is responding by flattening, emptying out and vanishing.

Mr. Rutter seems like he could be an intelligent writer, and we need every sharp writer we can get in the theater. One can hope that his criticism in the future will rise above what he turned in on this occasion.

Thursday, September 17, 2009

Phawker » Blog Archive » FRINGE REVIEW: How Theater Failed America:

Mike Daisey may be one of the great thinkers of our generation. He speaks truth to power, sometimes roaring, sometimes whispering, always entertaining. I can only add to the praise that’s already been heaped upon his shoulders. He’s saying what we already know, but are afraid to say publicly. In his show How Theater Failed America, he’s pointing out not so much that theater has failed America, but that America is failing theater. What makes this magical is not what he says, but how. Daisey’s relentless, nearly two-hour monologue holds two interwoven stories. One, with the stage lights exposing every nook and cranny of the bare stage at Philadelphia Theater Company, tells us about the business of theater. In his description, theaters have become massive machines, slouching forward churning out shows with no regard to community, artists, or social impact, and audiences are shrinking.

Mike Daisey may be one of the great thinkers of our generation. He speaks truth to power, sometimes roaring, sometimes whispering, always entertaining. I can only add to the praise that’s already been heaped upon his shoulders. He’s saying what we already know, but are afraid to say publicly. In his show How Theater Failed America, he’s pointing out not so much that theater has failed America, but that America is failing theater. What makes this magical is not what he says, but how. Daisey’s relentless, nearly two-hour monologue holds two interwoven stories. One, with the stage lights exposing every nook and cranny of the bare stage at Philadelphia Theater Company, tells us about the business of theater. In his description, theaters have become massive machines, slouching forward churning out shows with no regard to community, artists, or social impact, and audiences are shrinking.

Mike Daisey discusses faith and the global crisis: The American religion: Arts: Theater:

As Wall Street financial giants tumbled like a set of cheap dominoes last fall, Daisey was struck by an article about an island where the last surviving cargo cult was not only in existence, but actually thriving. Its inhabitants actually worship "cargo"—American materialism and commodities. They devoutly believe that an apocryphal American named John Frum, who visited the islands when the U.S. used it as a staging area during World War II, will return one day as a result of their prayers and ceremonies, bringing bounty and prosperity for all.

They wait for him, much as a fundamentalist Christian awaits rapture. And all day long, every Feb. 15, the islanders ritually celebrate the history of America in theater, dance and song.

As Wall Street financial giants tumbled like a set of cheap dominoes last fall, Daisey was struck by an article about an island where the last surviving cargo cult was not only in existence, but actually thriving. Its inhabitants actually worship "cargo"—American materialism and commodities. They devoutly believe that an apocryphal American named John Frum, who visited the islands when the U.S. used it as a staging area during World War II, will return one day as a result of their prayers and ceremonies, bringing bounty and prosperity for all.

They wait for him, much as a fundamentalist Christian awaits rapture. And all day long, every Feb. 15, the islanders ritually celebrate the history of America in theater, dance and song.

Ofay | Slog | The Stranger, Seattle's Only Newspaper:

Nobody knows where "ofay" comes from, but a few guesses. From the Online Etymological Dictionary:

Amer.Eng. black slang, "white person," 1925, of unknown origin. If, as is sometimes claimed, it derives from an African word, none corresponding to it has been found. Perhaps the most plausible speculation is Yoruba ófé "to disappear" (as from a powerful enemy), with the sense transf. from the word of self-protection to the source of the threat. OED regards the main alternative theory, that it is pig Latin for foe, to be an "implausible guess."

Another theory is that the Yoruba ófé was spoken to make the white person disappear. It also might come from the Ibibio word "afia," which means "light-colored."

Nobody knows where "ofay" comes from, but a few guesses. From the Online Etymological Dictionary:

Amer.Eng. black slang, "white person," 1925, of unknown origin. If, as is sometimes claimed, it derives from an African word, none corresponding to it has been found. Perhaps the most plausible speculation is Yoruba ófé "to disappear" (as from a powerful enemy), with the sense transf. from the word of self-protection to the source of the threat. OED regards the main alternative theory, that it is pig Latin for foe, to be an "implausible guess."

Another theory is that the Yoruba ófé was spoken to make the white person disappear. It also might come from the Ibibio word "afia," which means "light-colored."

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

Direct Evidence Of Role Of Sleep In Memory Formation Is Uncovered:

A Rutgers University, Newark and Collége de France, Paris research team has pinpointed for the first time the mechanism that takes place during sleep that causes learning and memory formation to occur.

It’s been known for more than a century that sleep somehow is important for learning and memory. Sigmund Freud further suspected that what we learned during the day was “rehearsed” by the brain during dreaming, allowing memories to form. And while much recent research has focused on the correlative links between the hippocampus and memory consolidation, what had not been identified was the specific processes that cause long-term memories to form.

A Rutgers University, Newark and Collége de France, Paris research team has pinpointed for the first time the mechanism that takes place during sleep that causes learning and memory formation to occur.

It’s been known for more than a century that sleep somehow is important for learning and memory. Sigmund Freud further suspected that what we learned during the day was “rehearsed” by the brain during dreaming, allowing memories to form. And while much recent research has focused on the correlative links between the hippocampus and memory consolidation, what had not been identified was the specific processes that cause long-term memories to form.

The Absurd critique and the materialist critique at the Fringe.:

Under the faintest of blue light, Mike parted the curtains and walked silently – like a ghost, only outlines of his plentiful figure visible – to the desk at stage front. He paused, and took a seat. Except for occasionally wild gesticulations, this was to be the only movement on stage for the next hundred minutes. And when the lights came up, Mike was off – like a horse race – launching into his piece with all the intensity I remembered.

How does one review a monologue? On must re-tell it, in parts.

Under the faintest of blue light, Mike parted the curtains and walked silently – like a ghost, only outlines of his plentiful figure visible – to the desk at stage front. He paused, and took a seat. Except for occasionally wild gesticulations, this was to be the only movement on stage for the next hundred minutes. And when the lights came up, Mike was off – like a horse race – launching into his piece with all the intensity I remembered.

How does one review a monologue? On must re-tell it, in parts.

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

Phillyist: News, events, music, film, and everything else cool about Philadelphia:

When I found out that Mike Daisey was going to be performing at this year's Live Arts Festival, I got super excited. I'd been wanting to see his monologue How Theatre Failed America for quite some time. And the things he had to say in that show really resonated with me.

I have to admit, I was a bit less interested in The Last Cargo Cult, until I learned what a cargo cult is. Daisey's monologue details his time spent living among the last cargo cult on the island of Tanna, who worship John Frum, a perhaps mythological figure who went to the island during WWII. The people who worship John Frum believe him to be a messiah, who will bring them wealth and other American goodies if they follow him. Daisey ties his experiences with the cargo cult into the current mess that is the financial market and leads his audience to think long and hard about this thing called money and why we value it—and our stuff—so much.

A kind of modern day Homer, minus the blindness, lyre, and dactylic hexameter, Daisey is a thoroughly engaging storyteller. He blends humor with poignant, spot on commentary, making you laugh and while you're laughing, actually think about what's going on. Both his monologues have closed now, but I really hope he comes back next year.

When I found out that Mike Daisey was going to be performing at this year's Live Arts Festival, I got super excited. I'd been wanting to see his monologue How Theatre Failed America for quite some time. And the things he had to say in that show really resonated with me.

I have to admit, I was a bit less interested in The Last Cargo Cult, until I learned what a cargo cult is. Daisey's monologue details his time spent living among the last cargo cult on the island of Tanna, who worship John Frum, a perhaps mythological figure who went to the island during WWII. The people who worship John Frum believe him to be a messiah, who will bring them wealth and other American goodies if they follow him. Daisey ties his experiences with the cargo cult into the current mess that is the financial market and leads his audience to think long and hard about this thing called money and why we value it—and our stuff—so much.

A kind of modern day Homer, minus the blindness, lyre, and dactylic hexameter, Daisey is a thoroughly engaging storyteller. He blends humor with poignant, spot on commentary, making you laugh and while you're laughing, actually think about what's going on. Both his monologues have closed now, but I really hope he comes back next year.

Monday, September 14, 2009

Philadelphia Free Library System is shutting down - Boing Boing:

The Philadelphia Free Library system is broke, and they're shutting it down, including cancelling "all branch and regional library programs, programs for children and teens, after school programs, computer classes, and programs for adults" and "all children programs, programs to support small businesses and job seekers, computer classes and after school programs" and "all library visits to schools, day care centers, senior centers and other community centers" and "all community meetings" and "all GED, ABE and ESL program."

Just look at that list of all the things libraries do for our communities, all the ways they help the least among us, the vulnerable, the children, the elderly. Think of every wonderful thing that happened to you among the shelves of a library. Think of the millions of lifelong love-affairs with literacy sparked in the collections of those libraries. Think of every person whose life was forever changed for the better in those buildings.

Think of the nobility of libraries and librarianship, the great scar that the Burning of Alexandria gouged in human history. Think of the archivists who barricaded themselves in the Hermitage during the Siege of Leningrad, slowly starving and freezing to death but refusing to desert their posts for fear that the collections they guarded would become firewood.

Think of the librarians who took a stand during the darkest years of the PATRIOT Act and refused to turn over patron records. Think of the moral unimpeachability of those whose trade is universal access to all human knowledge.

Picture an entire city, a modern, wealthy place, in the richest country in the world, in which the vital services provided by libraries are withdrawn due to political brinksmanship and an unwillingness to spare one banker's bonus worth of tax-dollars to sustain an entire region's connection with human culture and knowledge and community.

Think of it and ask yourself what the hell has happened to us.

The Philadelphia Free Library system is broke, and they're shutting it down, including cancelling "all branch and regional library programs, programs for children and teens, after school programs, computer classes, and programs for adults" and "all children programs, programs to support small businesses and job seekers, computer classes and after school programs" and "all library visits to schools, day care centers, senior centers and other community centers" and "all community meetings" and "all GED, ABE and ESL program."

Just look at that list of all the things libraries do for our communities, all the ways they help the least among us, the vulnerable, the children, the elderly. Think of every wonderful thing that happened to you among the shelves of a library. Think of the millions of lifelong love-affairs with literacy sparked in the collections of those libraries. Think of every person whose life was forever changed for the better in those buildings.

Think of the nobility of libraries and librarianship, the great scar that the Burning of Alexandria gouged in human history. Think of the archivists who barricaded themselves in the Hermitage during the Siege of Leningrad, slowly starving and freezing to death but refusing to desert their posts for fear that the collections they guarded would become firewood.

Think of the librarians who took a stand during the darkest years of the PATRIOT Act and refused to turn over patron records. Think of the moral unimpeachability of those whose trade is universal access to all human knowledge.

Picture an entire city, a modern, wealthy place, in the richest country in the world, in which the vital services provided by libraries are withdrawn due to political brinksmanship and an unwillingness to spare one banker's bonus worth of tax-dollars to sustain an entire region's connection with human culture and knowledge and community.

Think of it and ask yourself what the hell has happened to us.

Playbill News: Here at Last: A Preview of the Fall 2009 Off-Broadway Season:

Telling their stories solo and first-person will be: Mike Daisey, talking about his time on a remote South Pacific island whose inhabitants worship America at the base of a constantly erupting volcano in The Last Cargo Cult, at the Public Theater in December; Charlayne Woodard, discussing the ways she has mentored the children in her life, in The Night Watcher, starting Sept. 22 at Primary Stages; and Lynn Redgrave in Nightingale, a play inspired by her maternal grandmother, Beatrice Kempson, the least-known member of the Redgrave acting dynasty, starting Oct. 15 at Manhattan Theatre Club.

Telling their stories solo and first-person will be: Mike Daisey, talking about his time on a remote South Pacific island whose inhabitants worship America at the base of a constantly erupting volcano in The Last Cargo Cult, at the Public Theater in December; Charlayne Woodard, discussing the ways she has mentored the children in her life, in The Night Watcher, starting Sept. 22 at Primary Stages; and Lynn Redgrave in Nightingale, a play inspired by her maternal grandmother, Beatrice Kempson, the least-known member of the Redgrave acting dynasty, starting Oct. 15 at Manhattan Theatre Club.

Sunday, September 13, 2009

Jim Carroll, 60, Poet and Punk Rocker, Dies - Obituary (Obit) - NYTimes.com:

Jim Carroll, the poet and punk rocker in the outlaw tradition of Rimbaud and Burroughs who chronicled his wild youth in “The Basketball Diaries,” died on Friday at his home in Manhattan. He was 60.

Jim Carroll, the poet and punk rocker in the outlaw tradition of Rimbaud and Burroughs who chronicled his wild youth in “The Basketball Diaries,” died on Friday at his home in Manhattan. He was 60.

The mysterious equilibrium of zombies - The Boston Globe:

In the final scenes of “The Dark Knight” (spoiler alert!), the Joker gives the following choice to the passengers of two ferries: they can either blow up the other boat and save themselves, or themselves be blown up. If no one decides within a certain amount of time, both ferries are destroyed.

The typical moviegoer pretty much thinks one thing: Batman better show up now. But the mathematician immediately recognizes the Joker’s trap as a variation on the classic problem of the prisoner’s dilemma, where two individuals, each isolated in a prison cell, are given a choice: betray their friend and go free, or cooperate by saying nothing, and be given a short prison sentence. If each betrays the other, however, they will get a longer prison sentence.

This seminal problem in game theory has an important property: while cooperation is a more socially beneficial strategy, it is actually a more “stable” strategy for each person to betray the other, since this makes each better off independent of the whims of his friend. This behavior is known as a Nash equilibrium and is named after John Nash, well-known from the more obviously mathematical film, “A Beautiful Mind.”

In the final scenes of “The Dark Knight” (spoiler alert!), the Joker gives the following choice to the passengers of two ferries: they can either blow up the other boat and save themselves, or themselves be blown up. If no one decides within a certain amount of time, both ferries are destroyed.

The typical moviegoer pretty much thinks one thing: Batman better show up now. But the mathematician immediately recognizes the Joker’s trap as a variation on the classic problem of the prisoner’s dilemma, where two individuals, each isolated in a prison cell, are given a choice: betray their friend and go free, or cooperate by saying nothing, and be given a short prison sentence. If each betrays the other, however, they will get a longer prison sentence.

This seminal problem in game theory has an important property: while cooperation is a more socially beneficial strategy, it is actually a more “stable” strategy for each person to betray the other, since this makes each better off independent of the whims of his friend. This behavior is known as a Nash equilibrium and is named after John Nash, well-known from the more obviously mathematical film, “A Beautiful Mind.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)