Saturday, March 30, 2013

Friday, March 29, 2013

A few words in praise of gentlemen | Superfluities Redux:

It has been my privilege to meet personally several artists whose work I first encountered and admired from a distance. What has struck me most often is how gentlemanly, in all the respects I mentioned above, that the most admirable artists have been in my presence. However they may have conducted themselves in private, in public–or in meeting strangers like myself–they have been unswervingly considerate, amiable, and open-minded, even when their work, like William Gaddis’s, has been most scathingly critical and acidic.

I have also had the opposite experience. Meeting critics and artists whose work I’ve admired, then discovering them to be personally arrogant, dismissive, and discourteous, was something of a rude awakening in the exact sense of that term. Oddly, perhaps, when I return to their work after these personal interactions, I’ve found it to be more flawed, more uneven than before–testimony, perhaps, to the presence of the artist, or the person, in the art. (This, by the way, is quite different from my attitudes to the work of those more gentlemanly writers I describe above. I hold the work of these writers in the same high estimation that I originally did, of course, but no higher.)

It has been my privilege to meet personally several artists whose work I first encountered and admired from a distance. What has struck me most often is how gentlemanly, in all the respects I mentioned above, that the most admirable artists have been in my presence. However they may have conducted themselves in private, in public–or in meeting strangers like myself–they have been unswervingly considerate, amiable, and open-minded, even when their work, like William Gaddis’s, has been most scathingly critical and acidic.

I have also had the opposite experience. Meeting critics and artists whose work I’ve admired, then discovering them to be personally arrogant, dismissive, and discourteous, was something of a rude awakening in the exact sense of that term. Oddly, perhaps, when I return to their work after these personal interactions, I’ve found it to be more flawed, more uneven than before–testimony, perhaps, to the presence of the artist, or the person, in the art. (This, by the way, is quite different from my attitudes to the work of those more gentlemanly writers I describe above. I hold the work of these writers in the same high estimation that I originally did, of course, but no higher.)

Thursday, March 21, 2013

The long, slow decline of alt-weeklies | Jack Shafer:

The advertising shift from newsprint to Web is mirrored by a cultural shift. In my mind, the alt-weekly remains the perfect boredom-alleviation device. Waiting for a subway train? Pull one from your bag and it will entertain you. Your girlfriend is late for your date? The paper will keep you occupied. That beer and bag of nuts not distracting from life’s troubles as you mope on a barstool? The alt-weekly saves the day again.

But even a human fossil must concede that the smartphone trumps the alt-weekly as a boredom killer. How does a wedge of newsprint compete with an affordable messaging device that ferries games, social media apps, calendars, news, feature films, scores, coupons and a library’s worth of music and reading material? Ask a young person his opinion and he’ll tell you that nothing says “geezer” like a newspaper, be it daily or alt-weekly.

The advertising shift from newsprint to Web is mirrored by a cultural shift. In my mind, the alt-weekly remains the perfect boredom-alleviation device. Waiting for a subway train? Pull one from your bag and it will entertain you. Your girlfriend is late for your date? The paper will keep you occupied. That beer and bag of nuts not distracting from life’s troubles as you mope on a barstool? The alt-weekly saves the day again.

But even a human fossil must concede that the smartphone trumps the alt-weekly as a boredom killer. How does a wedge of newsprint compete with an affordable messaging device that ferries games, social media apps, calendars, news, feature films, scores, coupons and a library’s worth of music and reading material? Ask a young person his opinion and he’ll tell you that nothing says “geezer” like a newspaper, be it daily or alt-weekly.

Wednesday, March 20, 2013

Esquire Editor Explains: Women Are 'There to Be Beautiful Objects':

Here is what Alex Bilmes, the editor of Esquire UK, said at a panel discussion on feminism in the media (LOL) yesterday: "The women that we feature in the magazine are ornamental. That is how we see them."

"I could lie to you and say they're interested in their brains as well, but on the whole, we're not," he said. "They're there to be beautiful objects. They're objectified."

Here is what Alex Bilmes, the editor of Esquire UK, said at a panel discussion on feminism in the media (LOL) yesterday: "The women that we feature in the magazine are ornamental. That is how we see them."

"I could lie to you and say they're interested in their brains as well, but on the whole, we're not," he said. "They're there to be beautiful objects. They're objectified."

Tuesday, March 19, 2013

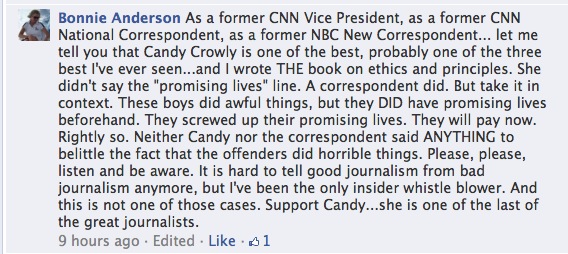

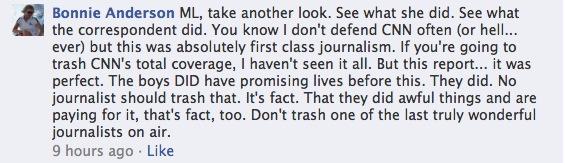

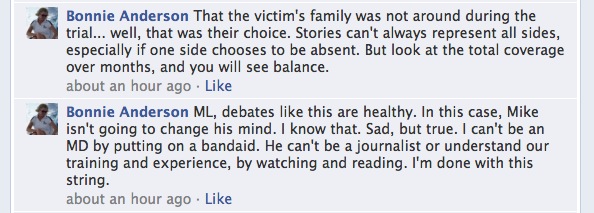

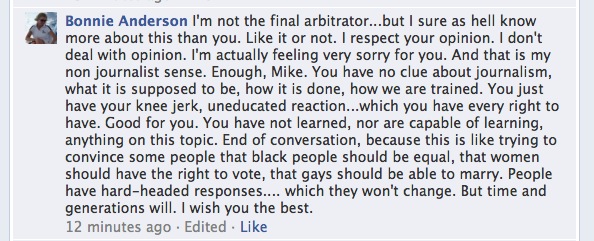

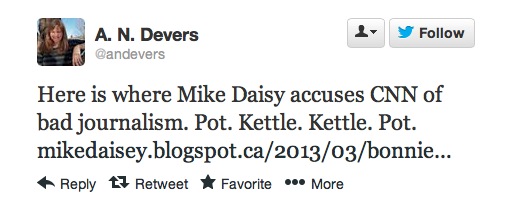

After yesterday's posting of my conversation with Bonnie Anderson about CNN's Steubenville coverage, this was inevitable:

I see this periodically about a variety of things I talk about, usually whether it directly applies or not. People love the Pot/Kettle trope, and mostly they love it because it's so fun to say on Twitter in one-word sentences. I get that. And as soundbites go, it's not too shabby.

I do think that it would work better if I had ever actually been a traditional journalist in any way, but I get it.

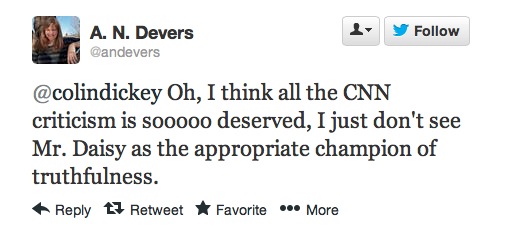

Her follow up tweet is what's interesting:

Good!

God save me from *ever* being "the appropriate champion of truthfulness". I can't imagine a shittier job title that I have never desired.

It ranks up there with other job titles that people have tried to give me over the last eighteen months: The Great White Savior of the Poor Beknighted Ignorant Chinese Peasantry. Or later, the Great Satan of Lying Whose Lying Lies Corrupt All Who Speak To Him.

Who am I?

I'm a working artist who has made a lot of work. Some of that work is well known—some of it is not. Some of it is topical. Some of it is lighthearted. Some of it numbers among the largest feats of narrative anyone has ever composed live. Some of it has been part of change. Some of it has been flawed, and was apologized for, and reformed.

So people can bring the snark if they wish—but what that snark says, more than anything, is that you don't know me and you never did.

I see this periodically about a variety of things I talk about, usually whether it directly applies or not. People love the Pot/Kettle trope, and mostly they love it because it's so fun to say on Twitter in one-word sentences. I get that. And as soundbites go, it's not too shabby.

I do think that it would work better if I had ever actually been a traditional journalist in any way, but I get it.

Her follow up tweet is what's interesting:

Good!

God save me from *ever* being "the appropriate champion of truthfulness". I can't imagine a shittier job title that I have never desired.

It ranks up there with other job titles that people have tried to give me over the last eighteen months: The Great White Savior of the Poor Beknighted Ignorant Chinese Peasantry. Or later, the Great Satan of Lying Whose Lying Lies Corrupt All Who Speak To Him.

Who am I?

I'm a working artist who has made a lot of work. Some of that work is well known—some of it is not. Some of it is topical. Some of it is lighthearted. Some of it numbers among the largest feats of narrative anyone has ever composed live. Some of it has been part of change. Some of it has been flawed, and was apologized for, and reformed.

So people can bring the snark if they wish—but what that snark says, more than anything, is that you don't know me and you never did.

Monday, March 18, 2013

When People Write for Free, Who Pays?:

Wealthy musician Amanda Palmer, who last year raised $1.2 million on Kickstarter to produce and release a record, recently used a TED talk to expand on the idea that artists should be willing to work for free. After relaying a story about how she used to be a street performer, Palmer, who is married to a very successful author named Neil Gaiman, told an audience of people who'd paid $7,500 apiece to be there that musicians shouldn't "make" people pay for their work, but rather "let" people pay for their work. She also explained that she found it virtuous when a family of undocumented immigrants huddled together on their couch for a night so that she and her band could have their beds, because her music and presence was a fair exchange for the family's comfort. After about 13 minutes of explaining why she is content with people giving her things, Palmer received a standing ovation.

Wealthy musician Amanda Palmer, who last year raised $1.2 million on Kickstarter to produce and release a record, recently used a TED talk to expand on the idea that artists should be willing to work for free. After relaying a story about how she used to be a street performer, Palmer, who is married to a very successful author named Neil Gaiman, told an audience of people who'd paid $7,500 apiece to be there that musicians shouldn't "make" people pay for their work, but rather "let" people pay for their work. She also explained that she found it virtuous when a family of undocumented immigrants huddled together on their couch for a night so that she and her band could have their beds, because her music and presence was a fair exchange for the family's comfort. After about 13 minutes of explaining why she is content with people giving her things, Palmer received a standing ovation.

Friday, March 15, 2013

Newspapering Is a Business: The Death of the Legendary Boston Phoenix:

There was the rail-thin cop reporter who cursed like a sailor and left work daily with the janitor, a cartoon of a Boston sports fan who sold pot while he emptied trash cans. The prototypical vampiric music editor who was immeasurably aloof and, pretty much, proudly, a giant know-it-all raving asshole. The bitterly meticulous arts editor, a man who, it was widely reported by the males on staff, would mutter "motherfucker" violently to himself at the urinal, a man who once broke down into a high-pitched screeching fit because someone had absconded his veggie-burger sandwich from the communal fridge.

And there was Clif Garboden. Until 2009, Clif was the Phoenix's senior managing editor, and he had been on staff for more than 30 years. He sat in a corner of the Phoenix newsroom, hunched at his computer with the posture of a question mark. His face had no angles. He wore sweaters over collared shirts and khaki pants. He enjoyed smoking and grumbling. His 1989 Buick Park Avenue, which he bought for $6000 with 43,186 miles on the odometer, was named Jerome. (I know this because he devoted an entire essay to the car.) He once received a death threat from a mime.

There was the rail-thin cop reporter who cursed like a sailor and left work daily with the janitor, a cartoon of a Boston sports fan who sold pot while he emptied trash cans. The prototypical vampiric music editor who was immeasurably aloof and, pretty much, proudly, a giant know-it-all raving asshole. The bitterly meticulous arts editor, a man who, it was widely reported by the males on staff, would mutter "motherfucker" violently to himself at the urinal, a man who once broke down into a high-pitched screeching fit because someone had absconded his veggie-burger sandwich from the communal fridge.

And there was Clif Garboden. Until 2009, Clif was the Phoenix's senior managing editor, and he had been on staff for more than 30 years. He sat in a corner of the Phoenix newsroom, hunched at his computer with the posture of a question mark. His face had no angles. He wore sweaters over collared shirts and khaki pants. He enjoyed smoking and grumbling. His 1989 Buick Park Avenue, which he bought for $6000 with 43,186 miles on the odometer, was named Jerome. (I know this because he devoted an entire essay to the car.) He once received a death threat from a mime.

Wednesday, March 13, 2013

The Deferential Spirit by Joan Didion | The New York Review of Books:

This quo vadis, or valedictory, mode is one in which Mr. Woodward has crashed repeatedly when faced with the question of what his books are about, as if his programming did not extend to this point. The “human story is the core” was his somewhat more perfunctory stab at explaining what he was up to in The Commanders. For Wired, his 1984 book about the life and death of the comic John Belushi, Mr. Woodward spoke to 217 people on the record and obtained access to “appointment calendars, diaries, telephone records, credit card receipts, medical records, handwritten notes, letters, photographs, newspaper and magazine articles, stacks of accountants’ records covering the last several years of Belushi’s life, daily movie production reports, contracts, hotel records, travel records, taxi receipts, limousine bills and Belushi’s monthly cash disbursement records,” only to arrive, not unlike HAL in 2001, at these questions: “Why? What happened? Who was responsible, if anyone? Could it have been different or better? Those were the questions raised by his family, friends and associates. Could success have been something other than a failure? The questions persist. Nonetheless, his best and most definitive legacy is his work. He made us laugh, and now he can make us think.”

In any real sense, these books are “about” nothing but the author’s own method, which is not, on the face of it, markedly different from other people’s. Mr. Woodward interviews people, he tapes or takes (“detailed”) notes on what they say. He takes “great care to compare and verify various sources’ accounts of the same events.” He obtains documents, he reads them, he files them: for The Brethren, the book he wrote with Scott Armstrong about the Supreme Court, the documents “filled eight file drawers.” He consults The Almanac of American Politics (“the bible, and I relied on it”), he reads what others have written on the subject: “In preparation for my own reporting,” he tells us about The Choice, “I and my assistant, Karen Alexander, read and often studied hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles.”

This quo vadis, or valedictory, mode is one in which Mr. Woodward has crashed repeatedly when faced with the question of what his books are about, as if his programming did not extend to this point. The “human story is the core” was his somewhat more perfunctory stab at explaining what he was up to in The Commanders. For Wired, his 1984 book about the life and death of the comic John Belushi, Mr. Woodward spoke to 217 people on the record and obtained access to “appointment calendars, diaries, telephone records, credit card receipts, medical records, handwritten notes, letters, photographs, newspaper and magazine articles, stacks of accountants’ records covering the last several years of Belushi’s life, daily movie production reports, contracts, hotel records, travel records, taxi receipts, limousine bills and Belushi’s monthly cash disbursement records,” only to arrive, not unlike HAL in 2001, at these questions: “Why? What happened? Who was responsible, if anyone? Could it have been different or better? Those were the questions raised by his family, friends and associates. Could success have been something other than a failure? The questions persist. Nonetheless, his best and most definitive legacy is his work. He made us laugh, and now he can make us think.”

In any real sense, these books are “about” nothing but the author’s own method, which is not, on the face of it, markedly different from other people’s. Mr. Woodward interviews people, he tapes or takes (“detailed”) notes on what they say. He takes “great care to compare and verify various sources’ accounts of the same events.” He obtains documents, he reads them, he files them: for The Brethren, the book he wrote with Scott Armstrong about the Supreme Court, the documents “filled eight file drawers.” He consults The Almanac of American Politics (“the bible, and I relied on it”), he reads what others have written on the subject: “In preparation for my own reporting,” he tells us about The Choice, “I and my assistant, Karen Alexander, read and often studied hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles.”

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

Finally: hear Bradley Manning in his own voice | Glenn Greenwald | Comment is free | guardian.co.uk:

Yesterday, former New York Times Executive Editor Bill Keller published a column which, while partially praising Manning's leaks, insinuated that the claims Manning made in his in-court statement about his motives and actions may be unreliable because they are not found in the logs of the chats in which he engaged with the government informant. That is factually false. As both Nathan Fuller and Greg Mitchell conclusively documented yesterday, Manning's descriptions match perfectly what he said in those chats when he thought nobody would ever hear what he was saying. That's what makes Manning's statements about his motives and thought process so reliable: they not only are consistent with his actions, but with everything he said when he thought he was speaking in private.

Whatever else is true, Bradley Manning is responsible for the most significant and valuable leaks since Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers. It is a cause for celebration that the US government's efforts to silence his voice, literally, have now been thwarted. Now, people can and should hear directly from Manning himself and make their own assessment. Whoever made this illicit recording (as well as the FPF in publishing it) acted in the best spirit of Manning himself: defying corrupt, unjust and self-protecting government secrecy rules in order to inform the world about vital matters.

Yesterday, former New York Times Executive Editor Bill Keller published a column which, while partially praising Manning's leaks, insinuated that the claims Manning made in his in-court statement about his motives and actions may be unreliable because they are not found in the logs of the chats in which he engaged with the government informant. That is factually false. As both Nathan Fuller and Greg Mitchell conclusively documented yesterday, Manning's descriptions match perfectly what he said in those chats when he thought nobody would ever hear what he was saying. That's what makes Manning's statements about his motives and thought process so reliable: they not only are consistent with his actions, but with everything he said when he thought he was speaking in private.

Whatever else is true, Bradley Manning is responsible for the most significant and valuable leaks since Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers. It is a cause for celebration that the US government's efforts to silence his voice, literally, have now been thwarted. Now, people can and should hear directly from Manning himself and make their own assessment. Whoever made this illicit recording (as well as the FPF in publishing it) acted in the best spirit of Manning himself: defying corrupt, unjust and self-protecting government secrecy rules in order to inform the world about vital matters.

Sunday, March 10, 2013

Staring Into the Abyss:

I was being tugged in two directions. My days were safe, practical, and obvious. My nights were dangerous, impractical, and not at all obvious. I started choosing the nights. My friends and family started to question my sanity. When asked why, the best I could explain was, "I have learned more from the last year than my prior twenty on Wall Street."

I was seeing firsthand, as my collaborator Cassie Rodenberg later would write, "How resilient people are, how, as brutal and bleak as life gets, people can find humor and friendship."

I was also seeing firsthand what Katherine Boo, the journalist, saw in the slums of India, "There's some way in which we would prefer not to see very clearly the immense gifts and intelligence of some of the people who live in our most abject conditions. Maybe there are some things at work in deciding who gets to be society's winners and who gets to be society's losers that don't have to do with merit."

I would come home filled with a mixture of empathy and anger. My Wall Street job started to seem less important.

I was being tugged in two directions. My days were safe, practical, and obvious. My nights were dangerous, impractical, and not at all obvious. I started choosing the nights. My friends and family started to question my sanity. When asked why, the best I could explain was, "I have learned more from the last year than my prior twenty on Wall Street."

I was seeing firsthand, as my collaborator Cassie Rodenberg later would write, "How resilient people are, how, as brutal and bleak as life gets, people can find humor and friendship."

I was also seeing firsthand what Katherine Boo, the journalist, saw in the slums of India, "There's some way in which we would prefer not to see very clearly the immense gifts and intelligence of some of the people who live in our most abject conditions. Maybe there are some things at work in deciding who gets to be society's winners and who gets to be society's losers that don't have to do with merit."

I would come home filled with a mixture of empathy and anger. My Wall Street job started to seem less important.

Friday, March 08, 2013

Thursday, March 07, 2013

Bloomberg Irked by Movies and Media - NYTimes.com:

“I don’t see any difference between a newspaper on the Internet and a blog. It confuses everything and takes away the difference. People are getting their news from sitcoms and from movies with a political agenda. They’re even getting information from games!”

(It should be noted that Mr. Bloomberg himself owns a media empire, including a financial news service, several magazines and a television station. His company is expanding and he has been rumored to covet The Financial Times.)

Mr. Bloomberg has previously complained about social media’s effect on government, notably during a trip to Singapore. Nowadays, “there is an instant referendum on everything,” he said in the M interview. “I’m worried how government can survive this.”

The interview, conducted by Terry Golway, has not yet been posted online. The print article is accompanied by an illustration of Mr. Bloomberg wearing a kind of Victorian barrister’s outfit and deems him “the man with no term limits.”

“I don’t see any difference between a newspaper on the Internet and a blog. It confuses everything and takes away the difference. People are getting their news from sitcoms and from movies with a political agenda. They’re even getting information from games!”

(It should be noted that Mr. Bloomberg himself owns a media empire, including a financial news service, several magazines and a television station. His company is expanding and he has been rumored to covet The Financial Times.)

Mr. Bloomberg has previously complained about social media’s effect on government, notably during a trip to Singapore. Nowadays, “there is an instant referendum on everything,” he said in the M interview. “I’m worried how government can survive this.”

The interview, conducted by Terry Golway, has not yet been posted online. The print article is accompanied by an illustration of Mr. Bloomberg wearing a kind of Victorian barrister’s outfit and deems him “the man with no term limits.”

Wednesday, March 06, 2013

The Charleston City Paper has awarded me its Best Liar award for its Best of Charleston 2013 issue.

Some would view this as a dubious honor, but not me. I'm learning to be gracious in my old age, and all great storytellers are great liars, just as all magic has deception at its heart. And since I didn't win an Obie or a Pulitzer last year, I've learned to gather my rosebuds where I may.

That said, the Charleston City Paper, in an attempt to tell my story, repeats something journalists often get wrong:

"The theatrical piece, which describes Daisey’s trip to China to visit a factory that makes Apple products, had aired on This American Life and described all sorts of atrocities, from underage workers to chemically induced medical problems to blacklisted workers. Once it turned out that Daisey had made up or exaggerated many of those details, TAL’s Ira Glass coolly eviscerated him in a March retraction episode of the radio show, making for what must have been the most uncomfortable hour of public radio ever made."

This is inaccurate. What would be more accurate would be to say, "Daisey had described events he did not actually witness."

Everything listed in the above paragraph: underage workers, hexane poisoning, worker blacklisting—all have been exhaustively documented at Foxconn and throughout the Special Economic Zone. From over a decade of NGO reports, stretching back long before I arrived on the scene, to the New York Times, CNN, and NPR stories that dropped after the TAL story. Even TAL's own retraction confesses that the worker conditions described are, in fact, accurate. They should be—they were narratively constructed from years of NGO reports on what those conditions are!

By failing to describe what was factual and what is not, journalists themselves muddy the water of the story. They are the ones who always had the tools at their disposal—the backstory of this is rich and well-documented. Telling the story accurately, which they keep saying is their highest aspiration, requires understanding the difference between a fiction about what has been personally witnessed, and what is true.

"Despite the public humiliation, Daisey performed the infamous monologue at the Spoleto Festival, and the audience loved it. Lies or not, it’s a masterful piece of work."

That's because, in every form it has ever existed, this has always been a true story. And audiences know that. And today, after the light that has been shone in on Foxconn and across the electronics industry, we all know it is more true than ever.

I'm proud of the work, and what it has accomplished.

And thank you, Charleston, sincerely, for this award.

Some would view this as a dubious honor, but not me. I'm learning to be gracious in my old age, and all great storytellers are great liars, just as all magic has deception at its heart. And since I didn't win an Obie or a Pulitzer last year, I've learned to gather my rosebuds where I may.

That said, the Charleston City Paper, in an attempt to tell my story, repeats something journalists often get wrong:

"The theatrical piece, which describes Daisey’s trip to China to visit a factory that makes Apple products, had aired on This American Life and described all sorts of atrocities, from underage workers to chemically induced medical problems to blacklisted workers. Once it turned out that Daisey had made up or exaggerated many of those details, TAL’s Ira Glass coolly eviscerated him in a March retraction episode of the radio show, making for what must have been the most uncomfortable hour of public radio ever made."

This is inaccurate. What would be more accurate would be to say, "Daisey had described events he did not actually witness."

Everything listed in the above paragraph: underage workers, hexane poisoning, worker blacklisting—all have been exhaustively documented at Foxconn and throughout the Special Economic Zone. From over a decade of NGO reports, stretching back long before I arrived on the scene, to the New York Times, CNN, and NPR stories that dropped after the TAL story. Even TAL's own retraction confesses that the worker conditions described are, in fact, accurate. They should be—they were narratively constructed from years of NGO reports on what those conditions are!

By failing to describe what was factual and what is not, journalists themselves muddy the water of the story. They are the ones who always had the tools at their disposal—the backstory of this is rich and well-documented. Telling the story accurately, which they keep saying is their highest aspiration, requires understanding the difference between a fiction about what has been personally witnessed, and what is true.

"Despite the public humiliation, Daisey performed the infamous monologue at the Spoleto Festival, and the audience loved it. Lies or not, it’s a masterful piece of work."

That's because, in every form it has ever existed, this has always been a true story. And audiences know that. And today, after the light that has been shone in on Foxconn and across the electronics industry, we all know it is more true than ever.

I'm proud of the work, and what it has accomplished.

And thank you, Charleston, sincerely, for this award.

Friday, March 01, 2013

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)